The Next Pandemic: A System for Prevention and Protection

Written 04/2018

In the summer of 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary was assassinated during a trip to Serbia, catalyzing one of the largest scale military conflicts in history. Aptly named “The Great War,” World War I lasted four years and claimed the lives of over 37 million people (“Killed, Wounded and Missing”). While it was tragic and horrifying in its own right, the first World War would not prove to be the deadliest killer of the 1910’s. That title would ultimately go to the Spanish Flu epidemic that afflicted the world in 1918. With the war over and peace finally restored, the flu season of 1918 began during a time of abundant optimism. However, as the days passed, it became evident that this flu virus was not ordinary. Strangely, although the flu usually beset the infant and the elderly, the virus seemed to be especially deadly among adolescents and young adults. Additionally, the mortality rate of the virus was 2.5%, much higher than the 0.1% expected of influenza viruses. The virus eventually spread to every continent and took the lives of an estimated 50 to 100 million people. This flu season was so extreme, that the average lifespan of those living in the US dropped by 10 years (Knobler).

Be it diplomacy or nuclear deterrence, post World War II, the world has developed methods to avoid large scale war, but has not developed an efficient way to combat health epidemics. Although medical technology and health security has advanced tremendously since the days of the Spanish influenza, the global community is frighteningly vulnerable to another disastrous pandemic. In the past decade, there have been many examples of near misses and close calls. The Ebola epidemic in West Africa affected over 28,000 people and resulted in more than 10,000 deaths (“Ebola Outbreak 2014-2015”). Fortunately, because Ebola can only be transmitted by contact with infected bodily fluids, the spread of the disease was severely impeded (“Ebola Virus Disease”). The Zika epidemic, which came into the global eye when it hit the Olympic host city in 2016, has caused panic due to the spike in cases of microcephaly, but in non pregnant females, the disease is rarely serious and almost never causes death (“Zika Virus”). Most recently, the 2017-2018 flu season has been severe, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) director, Dr. Anne Schuchat stating that, “[she thinks] the end of this season will end up being a bigger toll of disease than during [Swine flu]” (Fox). While governments are built with the main motive to protect their citizens, in the past half century, they have stopped after securing nuclear missiles. Many have ignored global epidemics, such as the Spanish flu, which endanger their citizens even more than the terrors of war.

Medical progress and technological innovation lull people into a false sense of security. Around the world, rates of infectious diseases have decreased dramatically, and populations are worrying more about noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). NCDs are certainly a cause for concern and it is necessary to dedicate resources towards treating and curing them, but not at the expense of ignoring the threat of a pandemic. An article by CNN states that population growth and urbanization, invasion of new ecosystems, climate change, and travel are among the reasons why it would not be unreasonable to expect a pandemic (Senthilingam). A study conducted by W. Bruine de Bruin in 2005 asked a group of public health officials and epidemiologists about the possibility of a bird flu pandemic. The subjects responded that in the next thirty years, there would be a pandemic that would infect 450 million to 2 billion, and kill 20 million to 180 million people (Bruin). Alarming in their predictions but firm in their convictions, these numbers serve as proof that the world needs a competent strategy to protect the global population in case of a pandemic.

Problem Definition

The world has developed immeasurably in every respect since the British Industrial Revolution, bringing extraordinary improvements in living standards and conditions. Unfortunately, this progress has also coaxed the world into a position vulnerable to a pandemic. Infectious disease rates have dropped precipitously, with smallpox eradicated and many others nearly eradicated. Yet zoonotic viruses still pose a threat, worrying public health officials and doctors. First transmitted from animal to human, zoonotic viruses account for many famous pandemics, such as Ebola, HIV/AIDS, and SARS among others. Zoonoses are notoriously unpredictable, which poses a particular threat to humans (Morse).

One of these potentially dangerous zoonotic viruses is the influenza virus; this may seem counterintuitive, as the flu is usually not severe enough for a hospital visit. However, there are many reasons for this, chief among them a rapid mutation rate and high infectivity. The CDC keeps surveillance of risky viruses, and at the top of their list of Viruses of Special Concern are the Avian Influenza A viruses. More specifically, H5N1 is known to be highly pathogenic and there have been reported cases of human to human transmission (“Viruses of Special Concern”). The World Health Organization (WHO) has a scale for pandemic influenza, consisting of four phases: Interpandemic, Alert, Pandemic, and Transition. H5N1 is currently in the “Alert” phase, indicating that surveillance and prevention responses are underway.

The impacts of such a large scale pandemic cannot be overstated; beyond just the massive lost of life, economies, infrastructure, cultures, and political systems would be negatively impacted in every country. Since corporations and governments seem to be motivated at least partially by economic growth, it is valuable to analyze the impact that an epidemic would have on the global economy. The immediate effect would be a decrease in the available labor force due to the illness. Following this would be an increase in the cost of business and a lack of interest in certain sectors of the economy (McKibbin). A paper from the Lowy Institute for International Policy concluded that “even a mild pandemic… is estimated to cost the world 1.4 million lives and close to 0.8% of GDP (approximately $US330 billion) in lost economic output… A massive global economic slowdown occurs in the ‘ultra’ scenario with over 142.2 million people killed and a GDP loss of $US4.4 trillion” (McKibbin). Revisiting the aforementioned study by Bruin, there is a significant probability of this “ultra” scenario (Bruin). Even the mild scenario would cause a disruption that would take years to recover from. The clear economic repercussions mean that every politician, health official, doctor, and citizen of every country has a vested interest in protecting the global community from a pandemic.

While every country would be adversely affected by an epidemic, ultimately the countries that would be hit hardest would be developing nations. Low income countries do not have the same health resources to enact a rapid response to a disease threat or to sustain a long drawn campaign against an epidemic (Oppenheim). This was evident even to Dr. Rudolf Carl Virchow, who stated in a 1848 article that “there [could] no longer be any doubt that such an epidemic dissemination of typhus had only been possible under the wretched conditions of life that poverty and lack of culture had created” (Virchow). From an economic standpoint, impoverished countries are disproportionately impacted by a pandemic than more affluent countries are, and that “as in most crises, developing countries are far more negatively affected than the larger economies of North America and Europe” (McKibbin). In addition to a lower capability of responding to an epidemic, lower income countries often have less political clout and power in the international community. In a situation where global coordination will determine the severity of an outbreak, poor countries will be unable to leverage their position as vigorously as rich countries.

Given the undeniable risk of a global pandemic, it should be reasonable to expect complex prevention strategies and a highly effective system ready in the case of such an event. Sadly, it seems that is not a safe assumption to make. As stated by Peter Sands, “compared with our position vis-à-vis other threats to human and economic security, such as war, terrorism, nuclear disaster, and financial crises, we are underinvested and underprepared. Pandemics are the neglected dimension of global security” (Sands). The global community is woefully unprepared for the onset of an epidemic virus. This is especially clear with recent action taken by the leaders of the United States. The CDC and USAID were collectively awarded almost $1 billion to fight the Ebola epidemic in West Africa (Yong). Officials “hoped dollars for the work would eventually be added into the CDC’s core budget,” but it seems that no funding is expected (McKay). The lack of funding is so severe that the CDC is scaling back operations in 39 countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where there was a recent Ebola outbreak. USAID is also expected to terminate and downsize programs (Yong). Just because Ebola is no longer an epidemic does not mean that there is not another pandemic coming. Early detection and response is essential to limiting outbreaks, but lack of funding prevents organizations and government departments from performing this indispensable service.

Methods

As with any issue associated with public and global health, there is no better place to look than the CDC and the WHO. While there is plenty to criticize about their actions, the global health governance has played an integral role in prevention and surveillance of emerging pandemic threats. Therefore, much of the up-to-date information on viruses come from the websites of these organizations. Because the dissemination of information plays an important role in fighting epidemics, global health organizations are vigilant in updating their websites to avoid confusion. This makes sources like the WHO and the CDC reliable for facts and figures relevant to this paper.

Additionally, this report partially focuses on governmental funding for organizations and aid programs. The governments of countries are critically important, as they serve as the main source of money for those fighting epidemics. Thus, any monetary decisions taken by governments will be found either through government sources or by trustworthy news outlets. The political nature of governance can lead to the spread of unreliable information. Subsequently, sources taken from news organizations and governments are carefully vetted. Any political leaning of a government or media company is taken into account, and information taken from these sources is analyzed for biases or prejudices.

Media outlets were also used for breaking news or updates on epidemics. Journalists are crucial due to their direct communication with the general populace; they use their audience to spread critical information about developments in evolving outbreaks. Media outlets, though, sometimes report misinformation in their haste to publish articles. Material taken from news articles was verified with government sources, health organizations, and other primary texts.

Finally, scholarly articles were used to present academic material and theoretical situations, and to verify other sources. Among the types of sources used, academic articles are the most reliable, as they are published in peer-reviewed journals. Even those that are not are vetted by the institution that funds their research. This makes the information taken from these sources accurate and reliable. There is a possibility that the information may be outdated, however, so newer sources were used whenever possible. Only anecdotal material was taken from older sources.

A total of thirty sources were used in the research for this paper. This may seem excessive for a 15 page report, but most the sources were used to provide evidence for any claims that were made. These sources provided mission statements from organizations and data for past pandemics. They include news sources, CDC and WHO facts pages, and websites for a variety of organizations. More theoretical information was supported with academic papers and institute reports. In particular, the report from the Lowy Institute for International Policy was helpful in analyzing the potential impact of an epidemic. Several sources were dedicated towards backing examination of governmental actions or pandemic impacts. An article from The Atlantic by Ed Yong proved indispensable in evaluating the lack of funding for the CDC and why that will inevitably prove to be dangerous. Additionally, Peter Sands’ report on global health security revealed why the current status quo of funding is insufficient for effective pandemic prevention.

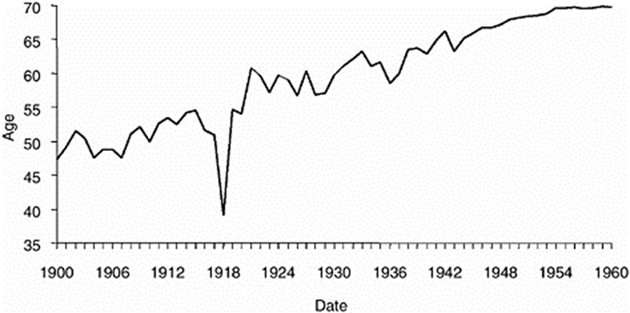

Fig. 1. United States life expectancy during the Spanish Flu (Knobler).

Figure 1 shows the life expectancy of those living in the US. World War I, which occurred during 1914 to 1918, is barely noticable on the graph. However, the sharp decrease in life expectancy during 1918 is impossible to miss. Life expectancy had been climbing steadily, but the Spanish Flu caused it to drop 10 years. Similarly in Africa, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has dropped the life expectancy of some countries over 30 years (Essex). For many of those countries, there still has not been a full recovery. If the global community can bring appropriate funding and resources towards pandemic surveillance and response, a precipitous drop in life expectancy would not be likely. Such a drop in life expectancy would have far reaching consequences beyond loss of life— there would be severe economic, cultural, and sociopolitical losses as well.

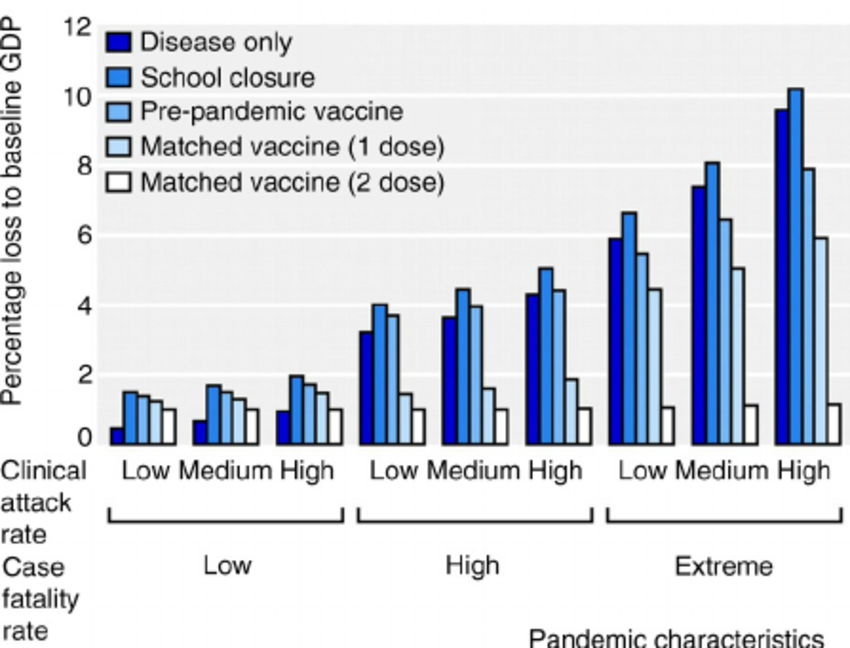

Fig. 2. Effect of a pandemic on the UK GDP (Bonanni).

This figure shows the economic effect of pandemics with different characteristics in the UK. A similar effect can be expected in other countries, with variability depending on whether it is a low-, middle-, or high- income country. During a worst case scenario, a pandemic with high clinical attack and case fatality rates, the UK GDP is projected to lose around 10%. In a world where even a 1% GDP drop generates a media frenzy, a 10% drop would be unimaginable. Even in a “best” case scenario, with low clinical attack and case fatality rate, the drop in GDP would be almost 2%. However, if a matched vaccine with two doses is found, no matter the characteristic of a pandemic, there would only be a 1% GDP drop. This only emphasizes the need for funding. With adequate funding, a vaccine can be developed either in preparation or in a timely fashion, avoiding the severe economic consequences of a pandemic.

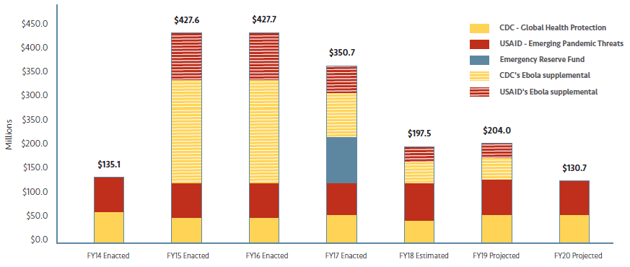

Fig. 3. CDC funding over 6 years (Yong).

The graph above shows the budget for the CDC and USAID from the 2014 fiscal year to the projected 2020 fiscal year. In 2014, the Ebola outbreak began, and the government granted the both CDC and USAID millions of dollars of additional funding. This proved essential in the fight against the spread of Ebola. However, that funding will soon disappear, bringing the budget back down to 2014 levels. Without the funding, CDC and USAID will be forced to scale down operations significantly, leaving the world again vulnerable to a pandemic. The CDC is pulling out of 39 countries, even where the Ebola outbreak was prominent. It begs the question: if funding had been ample enough for the CDC and USAID to conduct surveillance in West Africa, would the Ebola outbreak have been as severe? Would over 11,000 people have lost their lives? Funding is critical to prevention of and response to an epidemic, and these government agencies are being starved of it. Governments around the world should heed the warning of SARS, Ebola, and Zika, and invest in global health security.

Analysis and Causes

The nature of the relationship between viruses, animals, and humans that inevitably leads to a pandemic. There is no way of avoiding it— only detection and response will mitigate the destruction a pandemic would cause. Public health officials and doctors predicted a 100% probability that a large pandemic would occur in the next thirty years (Bruin). Even a mild pandemic would wreak havoc in the global economy. The devastation would be immeasurable, and the consequences would take decades to reverse. This should be enough reason for adequate funding of global health security and pandemic prevention. More money for pandemic preparation means improved research towards vaccines and cures for potentially dangerous viruses, a more robust reaction to outbreaks before they spread, and a larger capacity for treating the ill. These preventative measures would be able to stop a pandemic before it becomes too severe.

The US has historically been a global leader in epidemic prevention, but leadership at the moment is reluctant to fund organizations such as the CDC and USAID. As shown above in Figure 3, by 2020, CDC and USAID funding will drop to pre-Ebola levels. It should not take another global tragedy to grant these organizations money. Prevention of epidemics is far more effective than reaction. Unfortunately, the US has a quintessential case of what is called the Panic-Neglect cycle. According to Yong’s article, this cycle is when diseases cause panic and the government commits resources and money to the issue, but once the crisis is over, the resources and money disappear (Yong). The World Bank stated that “it is crucial that the financing is sustained: investing in preparedness is not a one-off, but an ongoing requirement” (World Bank). The next pandemic virus is not going to wait for countries to mount defenses and make preparations — the world must be prepared at any time to face the worst case scenario.

The US seems to have billions of dollars to spend on the military and antiterrorism efforts. Pandemics arguably pose a greater threat to national security than aggression from terrorists or foreign countries, but funding for pandemic prevention does not reflect this grave threat. The US has previously granted organizations sums of money that proved to be greatly beneficial in disease prevention. Obama committed $1 billion to the Global Health-Security Agenda, and saw tangible results. In Cameroon, response time for some diseases has decreased from eight weeks to 24 hrs (Yong). This statistic is illuminating in what funding accomplishes for health security. Rather than becoming entangled in the complexity of pandemic prevention at a global level, it is useful to focus specifically at local levels. Funding creates programs that revolutionize pandemic prevention at community levels, thus containing the disease and choking it before it can cause pandemic (Yong). From this narrow lens, it is hard to deny the value of money for fighting outbreaks.

Despite strong warnings by public health officials, the current US administration seems set on its goal to cut inefficiencies out of the government. Whether they are successful in this quest will be seen, but pandemic prevention is still an essential function of a government. Trump’s popular “America First” stance may hold water in other areas of society, but global health security is not one of those areas. Dr. Rebecca Katz remarked that “if [the] desire is to keep disease out of [the] country, the best way to do that is to contain it at the source” (Yong). This means that the US must be active in its efforts to control and monitor disease in other countries. There is no shortcut, no alternative for this. For at least health security, Trump should abandon his mantra. Funding for pandemic prevention not only protects US citizens, but provides a benefit to the entire world — a decision to grant more money to health organizations should not be difficult to make.

Solutions and Stakeholders

Everyone in the world is a stakeholder in the issue of pandemic prevention. In a worst case scenario, no one is too isolated or too rich to be affected. Therefore, everyone has a role in the preparation for a possible pandemic. At a downstream level, community members must stay vigilant in noticing signs of disease. During a pandemic, these members will be the ones on the front-lines, limiting spread of disease and implementing to the best of their ability prevention methods. Moving upstream, doctors serve as an interface between the public and public health officials. Beyond their duty to care for patients, they should be aware of and report signs of potentially dangerous viruses. Public health officials will take information given to them by doctors and the public, and their parent health organization will synthesize the information to give the scientific community research recommendations. These organizations will also communicate with governments on new developments or recommendations. Finally, at the top, governments, coordinated by the WHO, must work together to create a cohesive plan for responding to theoretical situations and imminent pandemics. Perhaps most importantly, governments must give the organizations appropriate funding to fully enact the best pandemic prevention system. This money will trickle downwards, giving organizations the surveillance tools and outbreak containment methods they need, which will allow them to better communicate with doctors, who then in turn give the public education and treatment. This hierarchy is not one of top-down dominance, nor is it a system that can be successful without the active participation of every member of society. In preventing pandemics, reporting by citizens is just as important as money from governments; the flow of information goes both ways, and a healthy system means timely reporting of and response to pandemics.

The most robust segment of this system is the “health organization.” This paper has focused mainly on governmental organizations such as the CDC, or USAID, but ultimately the greatest improvements to pandemic prevention have and will come from a variety of other organizations. PREDICT and the Global Virome project are both using novel technologies in virus identification and bioinformatics to track and discover potentially dangerous viruses (“PREDICT”, “About The Global Virome Project”). These organizations would be able to identify viruses and direct research long before a pandemic is imminent. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) seeks to create vaccines to prevent the spread and intensity of pandemic viruses (“Mission”). As seen from Figure 2, their work is essential for creating a best case scenario for a pandemic event.

In an increasingly electronic world, the internet often serves as a doctor to the public. Concerned citizens post their symptoms online hoping for answers. The Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) crawls the web for keywords, allowing the organization to effectively communicate with the public (“About GPHIN”). GPHIN has already found success. During the SARS epidemic, GPHIN reported cases of SARS a day before Chinese doctors did, and the WHO was able to confirm a case a week later (“Chapter 5: SARS: Lessons from a New Disease”). This early detection and rapid response prevented a devastating global pandemic of SARS (Enserink). SARS was the perfect recipe for disaster: the virus was infectious and boasted a mortality rate of over 10%. It could have been a worst case scenario, but actions taken by GPHIN and the global health community averted disaster. Newer organizations such as InSTEDD uses information from organizations like GPHIN to coordinate technological communication between software engineers, scientists, organizations, and governments (“iLabs”). This would allow full utilization of today’s advanced computer technology.

GHSA, as mentioned above, is a coalition of nations and organizations that creates pandemic prevention goals and taking steps to reach these goals. GHSA is an example of an organization that improves communication within the upstream levels of the public health hierarchy (“About”). Evidence from past epidemics have shown that there is an issue in the exchange of information between organizations, governments, and the global health government, WHO. During the Ebola epidemic, faulty communication between these levels led the WHO to react so late to the crisis that health experts were furious with the response (Kelland). GHSA meetings allow for coordination and rapid response strategies to be formulated before an epidemic strikes.

Every level of the global health security hierarchy must maintain a baseline level of preparedness and a constant level of alertness. At this junction, a weak link may be lack of funding. Bolstered by the internet, the public is perfectly capable of giving reports; evidence from past near-miss epidemics and optimistic reports have proved the competency of organizations. The world governments just need to provide the money to allow for a robust and healthy global pandemic response system. Adequate funding means that the next pandemic is SARS; lack of funding means that the next pandemic is the Spanish Flu. Complacency would be foolish, and failure to be prepared will draw scorn from future generations to come. We cannot sit back and let the next virus ambush us while we are defenseless. We may be susceptible, but that does not have to mean that we are unprepared. If the next pandemic is coming, funding must be allocated immediately to drive technological and scientific innovation. All political division, religious conflict, and xenophobia grow meek in the face of the threat a dangerous virus poses. Inspiration can be drawn from the global coordination to eradicate smallpox. Governments and people from all over the world joined forces to destroy a cruel disease that took millions of lives (“The Smallpox Eradication Programme - SEP (1966-1980)”). Smallpox eradication was not a miracle; it is evidence that full collaboration within the public health hierarchy can work miracles. Steps taken towards pandemic prevention is a commitment towards a better world— an investment both for today and for our posterity.

If you have any questions, comments, or suggestions, feel free to contact me at lauracao@usc.edu.